“When you look at the Internet, the Internet looks back at you.”1Kernighan, B. W. (2017). Understanding the digital world. Princeton University Press, p. 321

There are a couple of questions which have been bugging some of us here at SPAC. In the era of the personalized web, how does the browsing experience of an avid consumer of fake news differ from that of another person? More specifically, how does it affect the third-party content displayed in websites? And does a disinformation-filled browser history lead to different search engine results? In this blog post I will briefly discuss why studying online tracking might be beneficial for improving our knowledge about the spread of disinformation as well as the challenges associated with doing it ethically.

It is now common knowledge that third-party targeted content is a major funding mechanism for websites. Behavioral targeting of content allows companies and other entities to deliver their content to their target audiences through search engines (sponsored searches) or websites (ads or sponsored content).

For targeting users, advertising networks and other content providers need to build user profiles which require significant amounts of user data ranging from the user’s Geo-location, which can be inferred from the IP address, to the users’ interests, which are traditionally inferred from the browsing history and other data sources. While websites appear to be unitary entities stored in some web-server, some of the content displayed in our browser clients, say, the fonts or some images, once we visit a website comes from embedded third-parties. If given script access in websites, third-parties can track users across websites by assigning them unique identifiers. Typically, these unique identifiers are either arbitrary strings which are stored on the user’s device and associated with third-party domains (cookies) or computed, using JavaScript scripts, from properties of the user’s device which make it uniquely identifiable (fingerprinting).

Disinformation websites are not expected to be any different. Far from it. Anecdotes from Balkan teens to North-American suburban fathers suggest that it might be a profitable industry to be in. A recent report by the NGO Global Disinformation Index using a sample of 480 disinformation websites (tracked during a 5 month period) estimated that these websites were making millions in advertisement revenue. Similarly, there have been several accounts of targeted content being used for spreading disinformation, such as the targeted sponsored content repeatedly ran on Newsweek about the use of colloidal silver for treating covid-19. Our own preliminary research suggests that online tracking might be more pervasive in fake news websites in most categories of third-party trackers, but especially when it comes to trackers associated with advertising networks.

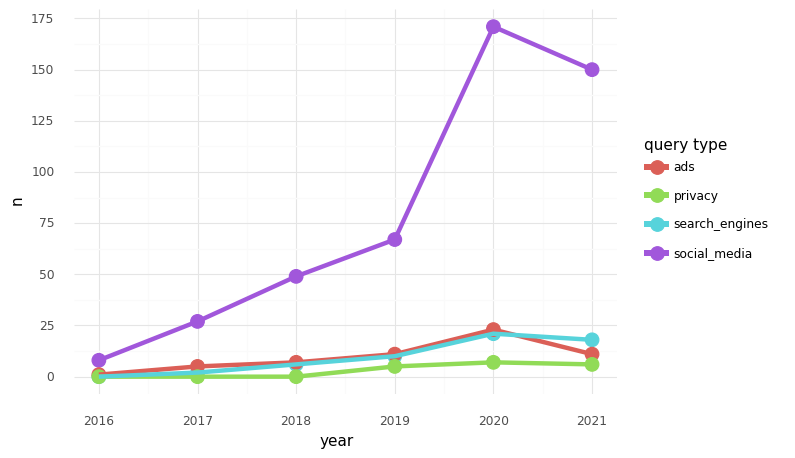

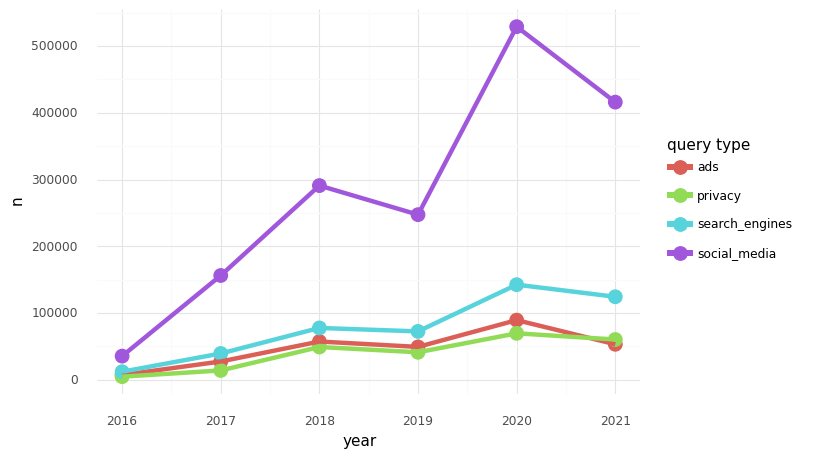

Nevertheless, online tracking and how it affects users’ experience in websites and search engines has received far less attention in policy and academic discussions around the topic of disinformation than other topics such as the role of social media platforms. For example, if one looks up the number of articles mentioning disinformation related keywords2More info on replicating this plot here along with keywords associated with social media, privacy, advertising, and search engines in a news article database such as mediacloud or in pre-print servers such as arxiv, we see that articles matching disinformation and social media related keywords contain a significant proportion of the hits.

arxiv Pre-prints

mediacloud News Articles

Figure 1: Number of articles (worldwide) matching disinformation keywords and keywords associated with ads, privacy, search engines and social media.

But how does one go around and study online tracking and the filter-bubbles associated with it? And how does one do it while respecting privacy? There seem to be three ways, each with underlying pros and cons. Firstly, we can ask people for their data or track users via voluntarily installed web-extensions. However, ethical research standards demand that such an approach should only be followed if it is truly privacy preserving and while there have been several positive developments in this front, it is still a crucial ethical boundary to keep in mind. A second approach involves using bots to mimic users and crawl the web from the point-of-view of “disinformation consumers” without using any actual personal data. However, this approach comes at the cost of an increased risk of bot detection by trackers and will never be “the real thing”. A third option, of course, is to have a good friend in high places (such as Google).

It goes without saying that researching disinformation on social media platforms is still crucial. Our objective here is to complement it by asking what happens when somebody clicks on that fake news website in their social media feed and decides to “do the research”.